|

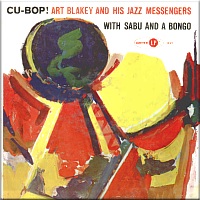

Art Blakey's bristling Jazz Messengers consists of Johnny Griffin, tenor; Bill Hardman, trumpet; Sam Dockery, piano; "Spanky" DeBrest, bass. The addition, conga drummer "Sabu" Martinez, like Blakey, has the molten soul of a dedicated percussionist. Like Blakey, he is wholly intense; and when he begins to play, he projects a fire that at times threatens to consume his instrument and himself. Like Blakey, Sabu too is a jazz drummer. He is very insistent on this point. "You can't play Latin conga to jazz," he declares. "At least, you shouldn't. I play the conga drum as a jazz instrument, not as a Latin addition. Using the conga drum this way is still relatively new, and very few conga drummers can express themselves as jazz musicians yet." Sabu was asked the primary differences between the way he plays jazz conga drum and the way he might play Latin conga drum. "I often leave more spaces in jazz, and I put more pressure on two and four. Actually, I feel jazz in two while in Latin music I have to feel the beat on all four beats pretty evenly. Another thing I do in jazz conga is to stretch my notes. I can deepen and stretch the beat by placing my hand heavier on the skin." Sabu is proud of a recent Art Blakey award of merit and valor. "Art said that I'm the only conga drummer who doesn't interfere with his drumming and who doesn't get in the way of the musicians when they're taking solos." This fervent conga drummer emphasizes another important aspect of his philosophy of jazz conga blowing. "You can express yourself on the conga drum in jazz as you would on a horn. I feel it as part of the group, like any other instrument, not as just a time-keeper." Howard McGhee, the renowned trumpet player who was listening to this conversation, included his view: '"The conga drum can be like any other instrument, like another saxophone or trumpet. It adds more color, in a way, than another horn, so that it not only boosts the rhythm but colors the whole band." Sabu is capable of becoming Toynbeeish about his beloved conga drum. "The conga drum," he assures those who will listen "is perhaps the first instrument in the world. Before the conga drum was a drum, it was a log, and logs were used to send messages." The subject has many ramifications through the eons, and we shall pursue it for the moment no farther. Sabu does not read music. "I feel the beat. I have been in jazz since 1947 and consider myself a jazz musician so I have no problem in feeling the rhythm and knowing what to do to express what I feel and to blend with the group.'' The first major influence on Sabu was the inflammatory Chano Pozo, the Cuban bongo and conga drummer who toured with the Dizzy Gillespie big band in 1948 and electrified musicians and audiences until he was cut down by a bullet that same year in a night club brawl. "Chano, whom I knew very well," Sabu remembers, "was happy he was part of jazz and happy that he was the one to introduce into jazz the real jazz possibilities of his instruments." Three days after Chano died, Sabu took his place with Dizzy. He has also worked with Charlie Parker, Mary Lou Williams, Blakey, Lionel Hampton, J. J. Johnson, Buddy De Franco, Benny Goodman, Thelonious Monk, Randy Weston, and other jazzmen. He would like to make his future in jazz, and has a quintet of trumpet, piano, bass, drums and conga drum. "I want to let people see and hear more of the conga drum as a jazz instrument." Sabu believes that this is the first jazz date on which two conga drums have been played simultaneously. "Before, they have used one; I wanted to get a taste of how two would sound. I tuned one to A and the other an octave higher. After being slapped a while, they might have come down a little in pitch but still an octave apart. Art tuned to the piano, and I tuned to Art. I'd rather tune to a skin or to a bass because it sounds more like a drum to me..." I have devoted this much space to Sabu because, first of all, it is his presence that differentiates this album from previous conclaves of Art Blakey and his Messengers. Secondly, Art's own background is already well and widely known, and has been detailed in a considerable number of liner notes. Very briefly, Abdullah Ibn Buhaina (his Moslem name) was born in Pittsburgh October 11, 1919. He has worked with Fletcher Henderson, Mary Lou Williams, Billy Eckstine (the honorable Eckstine 1944-47 modern jazz band), Lucky Millinder, Buddy De Franco, and has headed many units of his own. He has been a leader consistently in recent years, and this is his second Jazz Messengers unit of the '50s. (He had a big band titled the Messengers that he assembled intermittently from 1948-50.) In a Down Beat interview with this questioner in early 1956, Art explained why he was drawn to "The Messengers" as the name for a jazz band: "When I was a kid, I went to church mainly to relieve myself of problems and hardships. We did it by singing and clapping our hands. We called this way of relieving trouble having the spirit hit you. I get that same feeling, even more powerfully, when I'm playing jazz. In jazz, you get the message when you hear the music. And when we're on the stand, and we see that there are people in the audience who aren't patting their feet and who aren't nodding their heads to our music, we know we're doing something wrong. Because when we do get our message across, those heads and feet do move." Art's current sidemen represent a young blazing generation of jazzmen who grew up accepting the Bird-Dizzy-Monk-Bud revision of the jazz language as the natural way of speaking jazz. For many of them, it was the first jazz they heard and it made the most penetrating impact. Part of this younger generation continues to play directly within the Bird-Dizzy mainstream while at the same time trying to deepen, extend and continually re-energize the language. Johnny Griffin, a roaring tenor from Chicago who has strikingly impressed New York musicians in recent months, goes back farther in his acknowledged influences than a number of his contemporaries. According to Joe Segal, Metronome's Chicago voice, Griffin has listed Don Byas, Coleman Hawkins, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Lester Young, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie, Dexter Gordon, and Thelonious Monk as the musicians he prefers and presumably has [been] influenced by. Like Sonny Rollins, the dean of a section of young tenors, Griffin plays hard and hot and he possesses a conception that swings with compelling strength and rhythmic invention. Near 30, he is a valuable voice. Hardman, a crackling, spearing trumpeter, was born in Cleveland April 6, 1932. According to Ira Gitler, his influences were Benny Bailey (who was with Lionel Hampton in the mid-'40s), Miles Davis and Clifford Brown. Hardman worked with Tiny Bradshaw from 1953-55, and became a member of Charlie Mingus' uncompromising Jazz Worksbop in 1956. It was while with Mingus on a lashing, rainy night at Newport, that Hardman's conviction and emotional drive first impressed a large number of the oriented. He has become increasingly recognized through his work with Blakey in the past year. "Spanky" DeBrest has worked in and around Philadelphia; and Sam Dockery is an alumnus of a Buddy Rich group, among other units. The opening Shorty by Johnny Griffin is a virile head-shaker that sets and maintains a rolling, heated groove. Charlie Shavers' Dawn on the Desert begins with Johnny (not Griffin) stepping out of store-windows all over the oases but after that background camel-ride is happily over, the track settles down into a firmly pulsating, blues-shaded series of intent messages from the soloists. There is a conversation between Sabu and Blakey following Griffin that to his rhythm-struck listener, is an invigorating involving experience. Dizzy Gillespie's Woodyn' You has become as familiar to the young modern jazzman as Royal Garden Blues was to some of their predecessors, and it is played with the swift assertiveness of familiarity. The final Sakeena is named after a very new Art Blakey daughter, and seems to this listener to be an invocation to the new soul to bestir herself, to become and express herself, and to live fully. At any rate, it affects the mnsicians that way. The climax is again attained during a colloquy between Art and Sabu that comes to sound like a village of voices, instead of just two. This session not only swings; it multi-swings. -- Nat Hentoff, co-editor, Hear Me Talkin' to Ya and Jazz Makers (Rinehart) |

|

|

© 1997 Hip Wax